Hudson Cross-Country Challenge: Two Women Drivers Take the Wheel

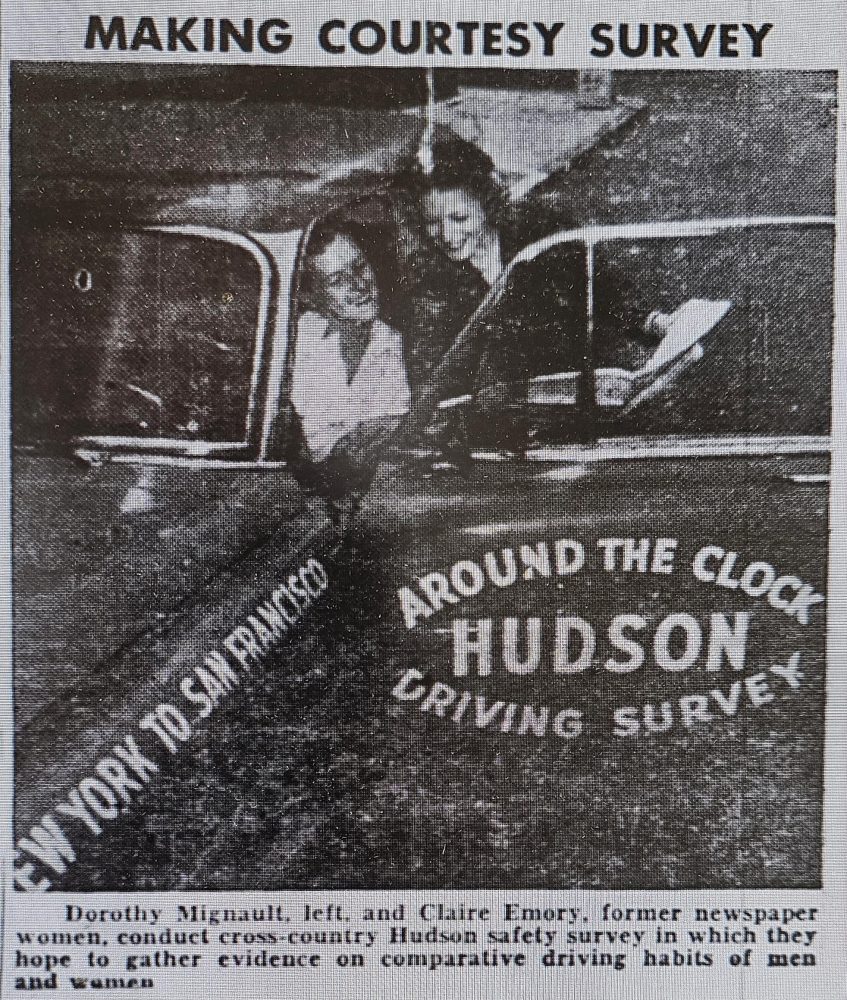

Held in the Merrick Auto Museum’s permanent archives is a 1953 Hudson’s proposal for a coast-to-coast publicity run—an idea that soon leapt off the page and onto America’s highways. In 1953, two women drivers brought the plan to life, re-enacting the legendary 1916 Hudson Super-Six endurance drive. With Dorothy Mignault and Claire Emory at the wheel, the journey took on a bold new twist: proving that women could master the open road with skill, courtesy, and confidence.

The Women Behind the Wheel

Hudson selected Dorothy Mignault of Kennebunkport, Maine, a former newspaperwoman and automobile agency manager, and Claire Emory of Connecticut, who hosted her own radio program in Stamford and had experience on stage and television. Both were excellent public speakers—ideal not only for the trip itself but also for the wave of interviews and appearances that would follow.

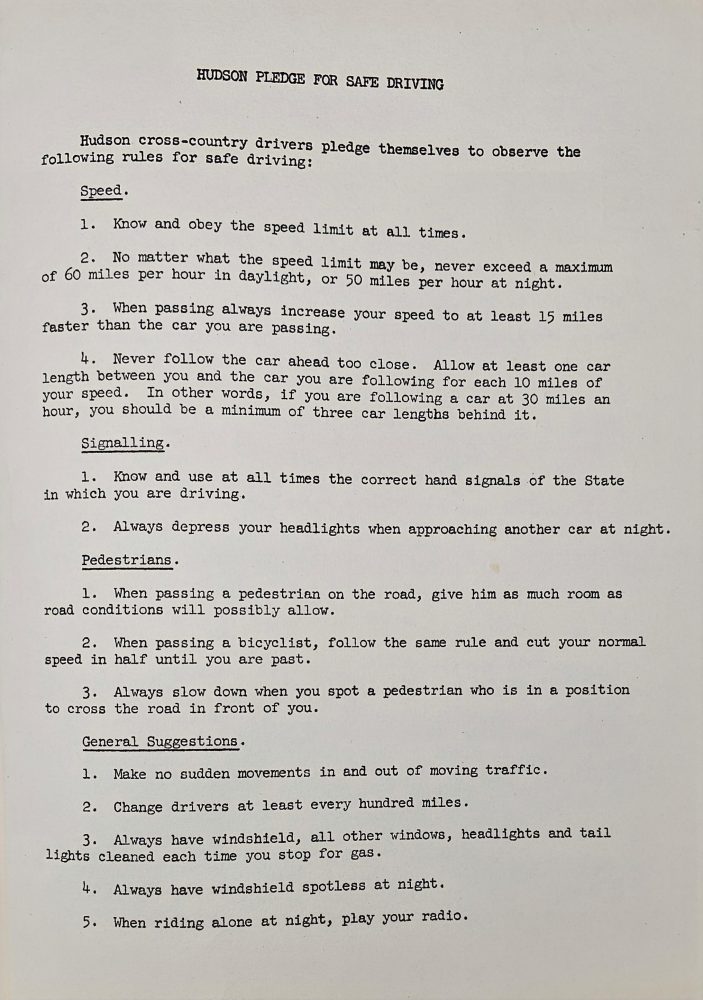

On July 27, 1953, the women set out from New York City, trading off driving duties so one could rest while the other steered westward. Just three days and eight hours later, they rolled into San Francisco. While this time easily outpaced the 1916 men’s record, Hudson emphasized that the run was no race—Mignault and Emory carefully observed all speed limits and traffic laws throughout their journey.

Publicity on the Open Road

From the start, Hudson designed the trip as both a test of endurance and a publicity showcase. Internal memos described the “battle of the sexes” angle that would “stir decided interest among radio program directors.” Along the route, local Hudson dealers were urged to host press conferences, radio spots, and safety promotions tied to the drive.

The women themselves leaned into the challenge. In a release to the press, Mignault explained:

“We hear repeatedly that men are far superior to women behind the wheel. Our findings positively challenge male driving superiority.”

Their message resonated. By the time they returned east in September, newspapers and radio commentators had picked up on their observations: male motorists committed thousands more traffic discourtesies than women during the trip.

A New Kind of Record

The New York Times summed it up in a headline on October 1, 1953: “2 WOMEN DRIVERS CALL MEN WORSE; Record on Cross-Country Tour Shows Male Autoists Were More Reckless on Road.” The women reported tallying 2,061 violations by men, compared to only 84 by women. Hudson’s own newsletter put it even more bluntly:

“Which Sex Drives Most Safely?” it asked, presenting the numbers as proof that women’s careful, law-abiding driving style deserved recognition.

Dealers, Safety, and Salesrooms

Hudson made sure the campaign tied directly back to its dealers. Field representatives visited towns in advance to arrange events, and dealers were encouraged to link promotions to safety. One suggestion: offer prizes for motorists who completed a Hudson safety checklist and wrote in with their observations. Radio stations could sponsor such contests as public service campaigns, further extending the publicity.

The result was a blend of spectacle, salesmanship, and social commentary—all centered on two women proving their skills behind the wheel of a Hudson Jet.

🚗 Trip Snapshot – Hudson Women’s Coast-to-Coast Drive, 1953

Drivers: Dorothy Mignault (Maine) & Claire Emory (Connecticut)

Car: Hudson Jet sedan

Route: New York City → San Francisco

Departure: July 27, 1953

Arrival: July 30, 1953

Elapsed Time: 3 days, 8 hours

Distance Covered: ~3,000 miles

Publicity Theme: “Battle of the Sexes” – proving women’s safe, courteous driving

Reported Findings:

Men drivers: 2,061 violations

Women drivers: 84 violations

From Publicity to the Showroom

Hudson’s coast-to-coast drive wasn’t just about proving women could hold their own on America’s highways—it was also about spotlighting the company’s newest car in the lineup: the Hudson Jet as well as the Hornet and Wasp. As the sales folders from 1954 proudly declared, the Jet offered “the world’s best ride with no useless weight” and combined performance, comfort, and economy in the lowest price field. With features like the Twin H-Power engine, Hydra-Matic drive, and Hudson’s trademark “step-down” design, the Jet was marketed as the ideal car for families, women drivers, and anyone who valued maneuverability and safety in the postwar motoring era.

The trip of Dorothy Mignault and Claire Emory gave dealers the perfect story to tell: not only was the Jet stylish and practical, but it had been proven coast-to-coast under the steady hands of two capable women.

Legacy of the 1953 Drive

Dorothy Mignault and Claire Emory’s trip was more than a reenactment—it was a statement. At a time when women drivers were often the target of jokes, Hudson gave them the spotlight and a platform to challenge assumptions.

For Hudson, it dramatized the company’s history, generated nationwide publicity, and reminded motorists that driving safely—and courteously—was as important as speed. It also tied seamlessly into the promotion of the Jet, giving the sales literature a living proof point: Hudson’s compact, powerful car could travel coast-to-coast with ease.

For Mignault and Emory, it was a chance to rewrite the narrative of who belonged on America’s highways. Their success became part of Hudson’s broader story of innovation, endurance, and forward-looking marketing—linking the heroics of 1916 to the modern realities of 1953 and beyond.

Want to see more stories of women drivers, daring road trips, and motoring history? The Merrick Auto Museum preserves rare literature and original documents that bring these stories to life. Explore our collection to see how automakers turned long miles into lasting legacies.